How to read a datasheet ?

So, since you started your journey into hardware making one word has been thrown around a lot: “datasheet”. You are not totally sure of what it is, but judging by how many times it is referenced by other engineers, you thought it must be very important. And you were right! Let me introduce you to this famous document.

The datasheet (sometimes called the spec sheet), is the document that lists every characteristic of a part or subassembly. It is provided by the manufacturer, who wants you to have every information you need to design a product using their part (and then buy lots of them).

Datasheets range from simple to very complicated. A small passive component such as a capacitor will have one or two pages of datasheets, up to about 1200 pages for the datasheet for a complex microcontroller! Obviously, you do not want to read so many pages, so you need to learn how to navigate effectively in this ocean of information.

Why do you want to read a datasheet?

Before you even download a datasheet, it is important to know why. Are you a programmer who wants to implement a software driver for a chip? An electrical designer picking the main parts of their next product? A reverse engineer trying to understand how an old board works? Parts of the datasheet that might be irrelevant for one of those situations might be crucial for another one.

Where do you even find those datasheets?

So now you need to find the document. I usually start by entering the name of the part I am interested in plus “datasheet” into Google. This is usually the quickest way to find what you are looking for. Make sure the part number in the PDF matches what you want, sometimes Google gives incorrect results!

Another way to find a datasheet is by going to the manufacturer website. This technique can be painful, as navigating the website is quite different for each manufacturer. You can usually find the documents from the page of the product you are interested in. This is unfortunately the only way to make sure you have every information about your part, as some manufacturer like to spread the information in various PDFs.

Finally, the last method is particularly useful when you are at the status of component selection. In this phase, you will be looking at a lot of different components, and searching the relevant datasheets takes a lot of time. Fortunately, large components retailer, like Digikey, usually offer datasheets for download from their product browser.

Like I mentioned some manufacturers keep all the information for one part in a single document, while others prefer to separate into several. Document intended for electrical engineers are usually what is called the datasheet. Software-related indications are typically in other documents, often named something like Reference Manual, Programmer’s manual, Programming model, etc. Sometimes the documents are shared across a device family. For example, the electrical information might be in the “STM32F407 datasheet”, while the programming documentation is in the “STM32F4 family reference manual”. Make sure you also download the errata; this document lists all the error and issues the manufacturer has discovered about their product and it helps to know about them.

Some manufacturers might not give you the datasheet right away; they might require you to give information about your company/product or sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA). I would try to stay away from such companies if possible, and only try to get their datasheets if you really cannot do otherwise. These behaviours are red flags: either the product is really new (the datasheet or the product itself still has issues) or the company wants to hide something (lack of performance?). Even if the company really just wants to protect their secrets it will come back to bite you later.

Anatomy of a datasheet

The first page(s) of a datasheet is called the Product Brief (see example below). It contains a list of all the features of a chip and the most important characteristics (power supply voltages, package, etc.). Start by reading those to make sure the chip suits your need. You can probably find typical applications of this chip here; see if your application is listed. If you don’t see the features you need on the brief, don’t waste your time on that part. In this section, you can also find the status of the chip (pre-release, active or obsolete) and the release date. Make sure you are not losing time with a very old part or something you won’t be able to buy in the next 18 months.

Some datasheets contain a section called Application Information or similar. In those sections, the manufacturer discusses the use of the product, usually with schematic and information regarding the choice of external components and the equations needed for your design. Sometimes the manufacturer will even suggest compatible parts to use for their design. If the datasheet does not contain such sections, look for documents called Application Notes (appnotes in short), which are separate document with the same purpose.

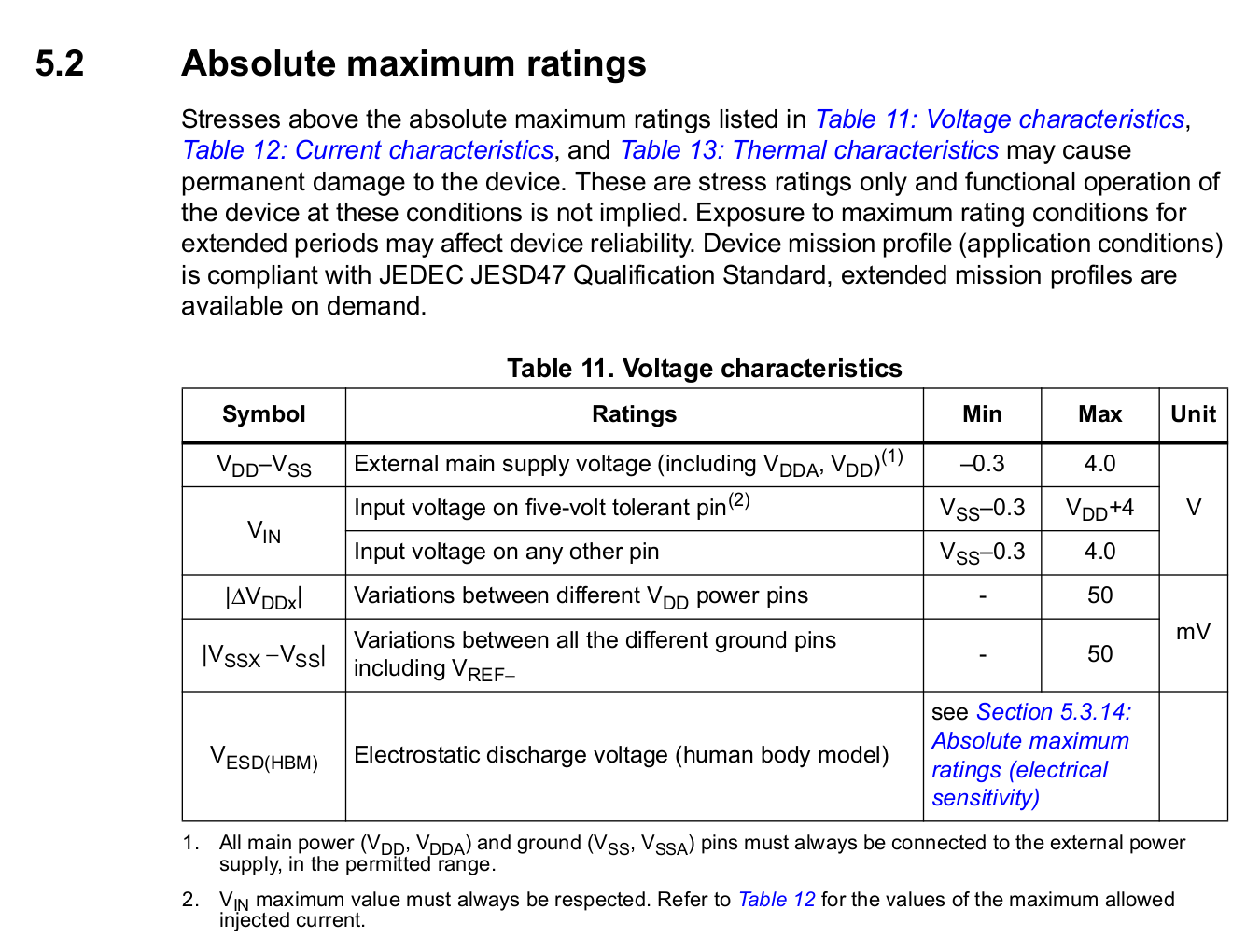

Next, find the section named “Absolute maximum ratings” (see example above). As the name implies, this contains the limits you must respect if you do not want to break the part. Study it carefully! The content of this section will vary a lot depending on the device you are studying, so it’s hard to give specific advice here.

When reading numerical values in a datasheet, you will see that it is quite common to have multiple values for one thing: usually a typical value and a range (min – max). Make sure your design is working over the whole range of possible values!

Random tips

When you do not know the exact name of what you are searching for, it is useful to look at the units: If you are searching for a time, simply skim the unit columns for something like nanoseconds.

There will be restrictions and conditions under which a given information is valid. Be careful, as they might be hidden in footnotes.

When looking at mechanical drawing, especially of chips, make sure you are looking at the correct orientation (from above or from below). Usually chip outlines are given from above, but you can sometimes be surprised.

When programming an unfamiliar device, I find it useful to print the relevant chapters from the datasheet. Then, take notes, draw schematics, write pseudo-code, highlight important sections etc. You cannot keep every important information in your head, and they will come back to bite you.

The datasheet is like a search engine. Use Ctrl-F a lot, and ask questions to the document. After a while you will know the kind of jargon used by your device’s manufacturer and you will be able to quickly find the detail you need.