Reverse engineering Swisscom's Centro Grande

Recently Swisscom (Switzerland’s biggest ISP) decided to give me a new box (modem + router + hotspot) since the previous one was already 7 years old. I was quite happy to get a new and hopefully 802.11N compatible router, but as I was just coming back from the CCC, I had to try to find what was inside. In the end I did not find the huge root-level backdoor I was hoping to find, but learnt a lot in the process. I published my notes on Github and got a few emails from fellow hackers trying to replicate my results. Now that I have a blog I might as well do an article about it, to have some content online !

Disclaimer 1

You may break stuff doing those manipulations. You follow this at your own risk.

Disclaimer 2

I am no Linux wizard. I might have skipped interesting things. Some parts may even be totally wrong. If you find something that should be changed, please tell me so ! Also, if you try to replicate those results or investigate further, I would be very happy to hear from you.

Getting the firmware

The first step of firmware analysis is getting the firmware. While that may sound obvious, there are actually quite a few ways to do it. The most complicated ones involve playing with JTAG or examining the chip under a microscope after opening it with acid. Fortunately for me, the firmware updates are quite easy to find on the web. To download it simply run the following command (Bluewin is the former name of the ISP part of Swisscom).

wget http://rmsdl.bluewin.ch/pirelli/Vx226N1_50033.rmtFirmware dissection 101

Firmware updates can be in a lot of various formats; the first step of the analysis must be finding out what is in the file. The tool I use to do this is called Binwalk. It can detect filetypes with a lot of different clues ranging from magic numbers in headers to entropy calculation. It can also detect different sections in a single archive, which will be very useful here.

Let’s start with a very basic analysis:

binwalk Vx226N1_50033.rmt

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

407 0x197 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 4194304 bytes, missing uncompressed size

27387 0x6AFB gzip compressed data, maximum compression, has original file name: "vmlinux.bin", from Unix, last modified: Mon Dec 20 16:43:51 2010So we first have some compressed data and then a compressed kernel (“vmlinux.bin” means Linux kernel). Let’s extract them into two different files so we can study them more in-depth. Once again binwalk is our friend:

binwalk Vx226N1_50033.rmt -e

cp _Vx226N1_50033.rmt.extracted/vmlinux.bin .What is in the vmlinux ?

So now we have a vmlinux, but it turns out it contains other stuff too. Let’s run binwalk on the extracted image to find out what is in there. I deleted some of the output to keep the log short.

>binwalk vmlinux.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

2289664 0x22F000 Linux kernel version "2.6.16.26 #1 Mon Dec 20 16:43:49 CET 20109 CET 2010"

2303103 0x23247F Copyright string: " 1995-1998 Mark Adler "

2316319 0x23581F Copyright string: " 1995-2002 Jean-loup Gailly "

2333484 0x239B2C Unix home path string: "/home/sj1scannpa/openrg/rg/os/linux-2.6/kernel/sched.c"

2333756 0x239C3C Unix home path string: "/home/sj1scannpa/openrg/rg/os/linux-2.6/kernel/fork.c"

#Snip...

2442560 0x254540 Unix home path string: "/home/sj1scannpa/openrg/rg/os/linux-2.6/net/8021q/vlan.c"

2639619 0x284703 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0xC0, dictionary size: 33554432 bytes, uncompressed size: 134217728 bytes

2795583 0x2AA83F LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x88, dictionary size: 65536 bytes, uncompressed size: 131072 bytes

2805760 0x2AD000 gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, last modified: Mon Dec 20 16:40:49 2010

2818048 0x2B0000 CramFS filesystem, little endian size 7077888 version #2 sorted_dirs CRC 0x584331ca, edition 0, 717 blocks, 412 files

9895936 0x970000 CramFS filesystem, little endian size 2293760 version #2 sorted_dirs CRC 0x5e4ab89, edition 0, 137 blocks, 33 filesNow that is quite a lot of information! What can we learn from it ?

- The kernel used in this is image is pretty old, but that is not really surprising. I didn’t use latest update and embedded systems developers are not known for being early adopters.

- The two copyright strings below are found in the deflate program in zlib, which is a common data compression library.

- I am not sure of the meaning of the home path strings. They were not detected by binwalk a few months ago when I started my analysis; I found them while redoing my experiments for this post. My best bet is that they are used in debug print strings which were expanded at compile time. OpenRG is a gateway operating software developped by Cisco and then sold to various device manufacturers. This is not really a good new as Cisco is pretty good at making secure embedded software.

- We have some compressed data, not too sure about what it is actually. The gzip part was build right before the kernel, so it probably has something to do. The first thing which came to my mind was some kind of initramfs. After playing a bit with cpio (the tool to extract ramfs images) I have the feeling that there is too much in there for just an initramfs. Maybe some kind of manufacturing mode ? I haven’t investigated too much into it, as it is probably useless once the router booted.

- Two filesystems using CramFS, which is specially designed for embedded use with flash. We can take a look at them because Binwalk can extract such filesystems. One of them contains what looks like kernel modules.

The other filesystem looks like a rootfs. It contains a few standard UNIX directories such as etc, bin or home.

Analyizing /etc

I will now take a look at what is in /etc.

For those who don’t know, etc is the place where most config files go in UNIX.

So far I only took a look at the configuration for OpenSSH server (/etc/ssh/sshd_config).

Port 22

AddressFamily inetThis only tells us that SSH is listening on every IPv4 adress on port 22 (default). The next interesting section gives us some informations about what kind of authentication is allowed :

PermitRootLogin yes

RSAAuthentication no

PubkeyAuthentication no

PasswordAuthentication yes

ChallengeResponseAuthentication no

PermitEmptyPasswords yesI don’t know much about SSH. What I know though is that authorizing root login via password is not really smart. Also empty password were explicictely turned on (PermitEmptyPasswords defaults to no). This is interesting, but I am not sure those are the settings used in production, maybe it is only for factory mode.

Playing with telnet

Enough static analysis, it is time to boot that router!

Running Nmap against it reveals that telnet is opened.

After trying a few user / password combinations, it seems that admin / 1234 works as login / pass.

We land in a configuration utility, but I think we can do better…

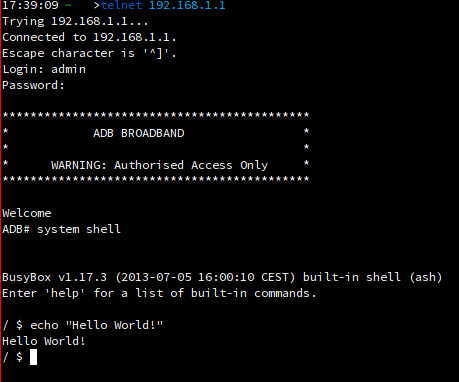

Getting a shell

- Connect to the router :

telnet 192.168.1.1. User:admin, pass:1234 - Go to factory settings :

factoryand enter the commandfactory-mode. This is a hidden command I found in an XML file in the routeur filesystem. - Your router will reboot. Once it has reboot, reset it using the reset button (at least I had to do it).

- The router won’t give you a DHCP lease anymore, so configure your network card manually.

- Telnet on it again, but this time use

adminas username and password. - Lauch

system shell. You will land on a real BusyBox shell ! Next step would be root access, which I haven’t managed to do yet.

To get back to normal mode, exit the shell and then run restore default-setting.

The router will reboot into normal mode.

Conclusion & Future work

The next step would be “rooting” the device. This could be done in a few ways, for example exploiting vulnerabilities in setuid programs. The list of such executables can be found on the Github repository.

Another exploit path would be to use a JTAG debugger to get root access. This is cheating, but it would definitely be useful to do some debugging or play a bit. I ordered a JTAG adapter, so if I have some time when no one depends on the router I will try to do it.

While browsing throught the firmware I read a few things about how USB devices are handled (the router has two USB ports). The two device type which are the most interesting to me are device storages and serial adapters. Apparently the router can spawn a network share when we plug in a usb key. I haven’t tested it yet, but it may be vulnerable to symlink traversal for example. The serial adapters are also handled, but I am not quite sure of what they do. My guess would be that they provide some sort of debug shell. I still need to inveestigare here.

This is where I stopped playing the router. It is now deployed to my “production”, and my family will be very angry if I reverse it now. If anyone is interested in replicating those results or going further, I would be very interested to discuss it with you (my email is on Github).